SBI Insights

Welcome to the hub of bioprocessing insights

Articles

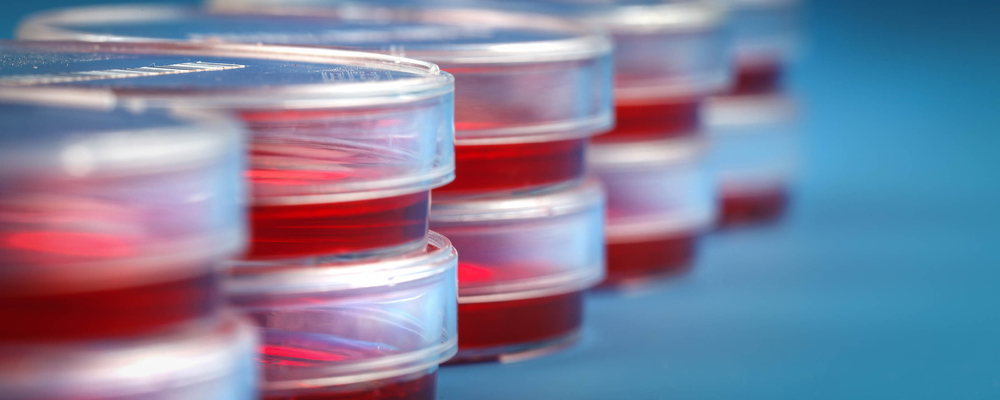

Oxygen in Mammalian Cell Culture

April 7, 2025Mammalian cell culture experiments have been instrumental in shaping biomedical research, leading to groundbreaking discoveries about physiological processes and disease mechanisms. These experiments have been critical not only for understanding the origins of diseases but also for developing treatments. Undoubtedly, cell culture remains a cornerstone of both basic and applied biomedical…